NBG offers sunnier outlook on inflation in 2022

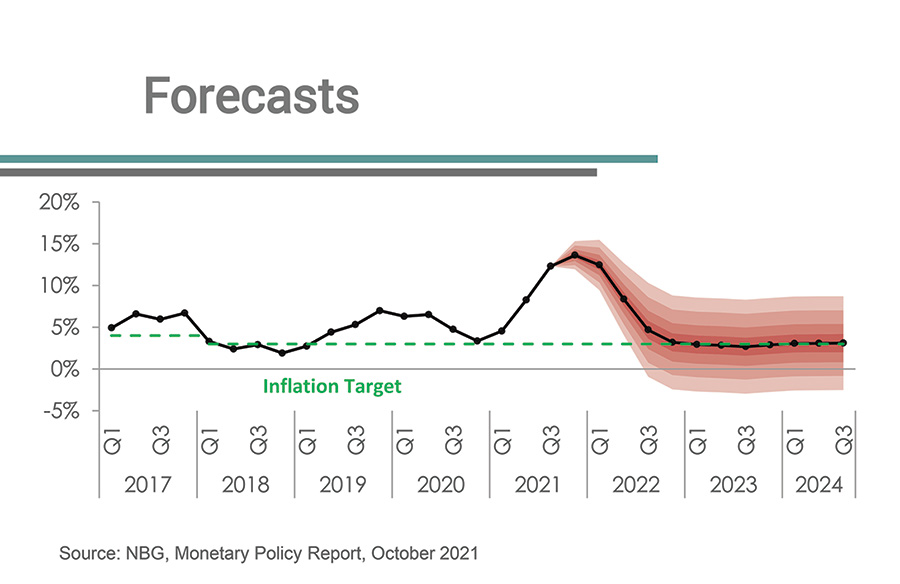

As autumn turned to winter and colder temperatures set in, prices in Georgia only continued to heat up. The country ended 2021 with an annual inflation rate of almost 14%, its highest level since 2010. But while this statistic has caused unease among some economists and a strain on the wallets of many Georgians, the NBG’s latest monetary policy report attributes the majority of Georgia’s inflation problems to exogenous one-off factors, offering a forecast of lower inflation starting in the first quarter of 2022.

What’s causing inflation in Georgia?

Georgia’s inflation problem can be more easily understood by making a distinction between the rate’s core and headline components . Headline inflation, which measures total inflation in the economy and includes prices of commodities that are often volatile, amounted to 13.9% in December. However, the NBG’s Head of Macroeconomics and Statistics Shalva Mkhatrishvili says that this inflation is largely based on temporary and external factors. “The predominant reason we see inflation acceleration right now is due to the international price of commodities. If you net out the more volatile components of inflation like food, fuel, and tobacco prices, you see that core inflation is around 6%. It’s this core inflation rate that gives us a better idea of where the economy is going in the medium term.”

Supply-side factors, like an increase in global transportation and logistics costs, have significantly increased the prices of imported goods for Georgians. The NBG estimates that these factors accounted for more than 5% of December’s 13.9% annual inflation rate.

One of the largest supply-side factors contributing to the current inflation rate is the global spike in food prices over the last year. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, September 2021 food prices in international markets increased by 33% in USD terms compared to the same time in 2020. While people all around the world have been impacted by inflation, consumers in certain countries like Georgia have felt the pinch more due to the higher share of food in their consumer basket (currently 29%) compared to more developed economies.

Mkhatrishvili contends that a look at the country’s imported inflation rate supports the argument that inflation in Georgia is largely being driven by external factors. It also rules out the GEL foreign exchange rate as a major factor driving inflation. “Annual imported inflation in December was over 20%, while the lari registered an annual appreciation since last December. This indicates that it is not the exchange rate that is significantly contributing to inflation but the prices of commodities, which we can see have increased in the international markets in terms of USD.” In its monetary policy report for 2021 Q3, the NBG put the exchange rate’s estimated effect on inflation at just half a percentage point, a figure that has continued to decline throughout the winter months.

So, if Georgia’s inflation is largely a result of external factors, why has domestic inflation increased as well? This can be ascribed to supply chain issues felt by Georgian producers as well as their use of commodities as inputs .

“Domestic inflation is higher than we’ve seen previously but still much lower than imported inflation. Part of the reason it has grown is because of the open nature of our economy, meaning global supply disruptions and higher costs of intermediary inputs have pushed up the prices of domestically produced goods,” says the NBG’s Mkhatrishvili.

Another surprising factor that’s impacted inflation significantly in the last few months? Utility fees. This dramatic price differential is the result of a subsidy program introduced by the Georgian government during the winter months of 2020 to alleviate financial pressure on the population after Covid-19 majorly disrupted the economy. The program, which covered the natural gas costs of more than a million households and the electricity fees for more than 600,000 households, deflated Georgian residents’ utility prices for four months, starting in November 2020 . A year later, as the cold set in and Georgians switched on the heat in 2021, the jump in prices created a base effect, which was reflected in higher headline inflation. According to Geostat, utility fee prices contributed 3.6% to inflation in December, a statistical factor that the central bank anticipates will continue to have a substantial impact on inflation until the spring of 2022.

Will warmer weather bring a cooldown in prices?

As the winter cold thaws and spring emerges, so should price stabilization, according to NBG forecasts. The NBG noted in its 2021 Q4 monetary policy report that the utility subsidy’s base effect is expected to expire one year from its conclusion in March 2022.

Mkhatrishvili also says economists are expecting that commodity prices won’t continue to increase like they have been. “Even if commodity prices don’t go back to pre-pandemic levels, we don’t anticipate them to continue increasing at this rate. If that’s the case, then inflation will decline.”

The NBG’s Head of Macroeconomics and Statistics also emphasizes that monetary policy can only address part of the country’s current inflation challenges, noting that attempting to tackle supply-side shocks like global price increases in fuel and food can do more harm than good for the economy.

“When looking at inflation from a macroeconomic perspective, we have to ask, ‘Is this something that is caused by monetary policy and is there something monetary policy can do to alleviate the situation?’ From this perspective, there is not much monetary policy can do to affect international prices. If we were to tighten monetary policy too much to try and address this, it could really hurt the productive capacity of the country.”

“However,” he notes, “when these one-off factors affect prices the way they did, it can affect medium and long-term expectations for inflation.” To combat these second-round effects and “address the associated risks to the economy, it is necessary for the NBG to tighten its monetary policy, which it did when it raised its benchmark interest rate to 10.5% in December [up from 8% at the beginning of 2021].”

Mkhatrishvili says these two combined factors – anticipated stabilization of exogenous factors and tightened monetary policy – have led the NBG to predict that inflation will start to decline in Q1 2022.

In its October 2021 monetary policy report, the NBG projected that after a continued decline in inflation during Q2 and Q3, the country should hit its target rate of 3% in Q4, according to the central bank’s baseline forecast. With this will come a gradual decrease of the benchmark interest rate, which is expected to to hit 8.0 – 8.5% at the end of 2022, offering hope that sunnier days will bring more stable prices.