Crafting khanjalis – Georgia’s traditional dagger finds new favor abroad

The Khanjali, the most iconic and requisite part of Georgian national dress for men, have been made in the Caucasus for thousands of years. Today, growing interest from international collectors is rapidly revitalizing this Georgian craft sector.

The khanjali is one of a large family of Georgian knives, daggers, and swords. Today, they are popular with collectors internationally, with prices of beautifully crafted new, custom-made ones running into the tens of thousands of dollars. The designing and forging of modern khanjali, Satevari, or Qama, is galvanizing many new Georgian masters and blacksmiths as well as exhibitions that draw thousands, rapidly revitalizing this Georgian craft sector.

Georgia, with its embattled past, has needed more than its fair share of bladed weapons throughout its history. At times of mountain warfare, even its women were obliged to carry them. Historically, they form an integral part of Georgia’s mythology, which was recognized by the 19th century Russian poets Alexander Pushkin and Michael Lermontov, who both addressed celebrated poems to the khanjali. Today, these are more akin to ornamental art objects than practical instruments.

Craft revival

A fashionable revival of interest in expensive, individually crafted knives has also been seen by U.S. and European craftsmen, but these are mostly for chefs or inspired by Japan’s sushi knives. Although priced at up to $1,000 or more, they are mostly purely practical and rarely have the beauty of design of ancient Georgian knives. Georgian prices range from upwards of a few hundred lari, with old ones bringing thousands at auction houses like Rock Island Auction Company and the U.S.-based auction house Noblie; custom-made new ones can go for even more.

Georgian interest in its traditional knives is growing. The Knife Makers & Collectors Association of Georgia has 38,000 followers on Facebook, with enthusiasts coming from all around the world. The association held a second annual exhibition last October in Tbilisi, drawing around 1,500 attendees. A third is planned for the autumn of 2024. Jaba Bokuchava, the association’s founder and a life-long khanjali enthusiast, believes there are now as many as 150 makers of knives in Georgia, although probably only ten or fifteen could be described as masters.

For several years, Jaba Bokuchava has been working to consolidate interest in Georgian knives, daggers and swords into an organization that can help promote the crafts and promote compliance with regulation and police concern about the spread of knives. As he said, even in the hard times, such as at the end of the Soviet Union, masters were still working and have continued since. These days, a very wide range of examples can be found in corners of Georgian art galleries, such as Vanda Gallery in Sololaki, or as part of traditional dress at Samoseli Pirveli in Tbilisi’s Leo Kiacheli street.But until he set up the association and its website and launched the annual exhibitions, this had become almost a hidden craft.

The association now numbers several hundred Georgian and overseas members, who regularly correspond online with each other to swap notes and trade.

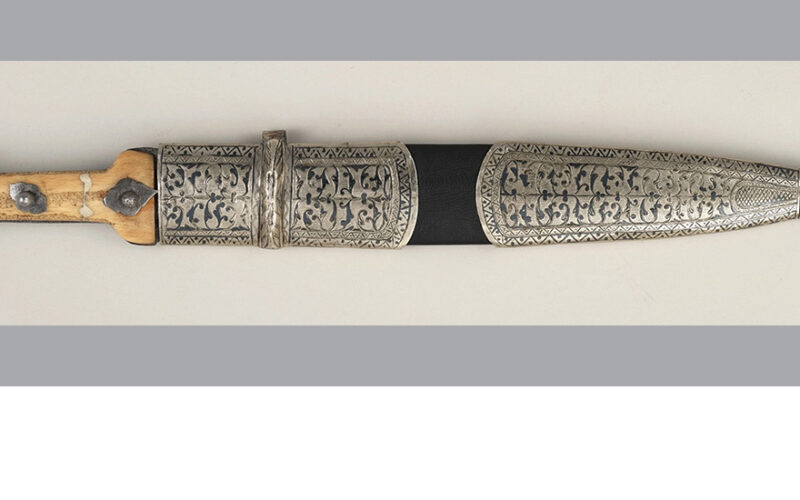

The range of new design is widely varied – from the strictly utilitarian to ones whose complex designs outshine even those of centuries ago. The khanjali dagger is a double-edged blade often featuring a single, off-set groove on each side of the blade, and its handle has a guard and pommel extending out of it. Similar in shape to the ancient Roman gladiators’ gladius, the Scottish dirk, or ancient Greek xiphos, khanjali were usually highly engraved with gold and silver inlaid designs – and sometimes embedded gemstones. The most valuable copies of these, the gem-studded ones especially, can be found today in Georgian specialist jewelers shops, such as goldsmith Zarapkhana’s outlets in Tbilisi and Batumi. But most contemporary masters follow tradition and decorate their knives with inlays and engravings.

An age-old instrument

The earlier name was Satevari, examples being found dating back to the 3rd century; these were small as they were made of copper and bronze, which did not allow for long blades. By the 18th and 19th centuries, production of khanjali and other bladed weapons in Georgia was booming, demand coming not just from the Georgian and Caucasian mountain people, but also from Iran and countries further east. The Tbilisi blacksmiths were famous for the hardness of their metal and were not only Georgians, but Dagestanis, Circassians, and Armenians. Ancient specimens can be found in museums around the world, such as in the New York Met, in Poland, and, of course, in Russia. Some khanjali they made were from swords whose blades had been broken.

The metal also has its legends. The most famous steel in medieval times was bulat steel, a very tough type of high-carbon but flexible steel that historians believe was first used by nomads many centuries ago, but the recipe for that seems to have disappeared with time. Similar was Damascus steel, whose original recipes also disappeared, the feature of which was its distinct pattern of pale and shadowy grains. Today, blacksmiths and knifemakers produce a type of Damascus steel by using a pattern welding process to combine two different steels into a singular design.

An associated tale is that in the first half of the 19th century, the most famous weaponry blacksmiths were the Georgian Elizarashvili family in Tbilisi. Giorgi Elizarashvili inherited from his ancestors the family secrets of processing exceptionally strong steel. This secrecy was strictly maintained, but (and here the stories vary, either willingly or because of coercion) in 1828, the family shared the secrets with the Russian Zlotousk factory by order of the Russian Emperor, Nicholas I. However, according to this version, when Elizarashvili died, he was found to have taken the knowledge of one vital ingredient with him. So, that type of metal also disappeared!

Modern makers

In recent history, one of Georgia’s most famous masters has been Teimuraz Jalaghania, now in his 80s and a practitioner of the traditional craft of Damascening – laying different metals into one another, typically, gold or silver into a darkly oxidized steel background – for decades. He has been teaching for nearly 50 years, and has passed on his skills to many. His story is told on the online craft platform Homo Faber, which is funded by the MichaelAngelo Foundation.

The scope to use these skills is wide, as shown by the career of Gocha Laghidze, who describes himself as a maker of “traditional arms and armor,” although in fact he does much more than that. As recounted in European Blades Magazine, he is, indeed, a metal artist. He forges sabers, swords, armor, and helmets; makes coats of mail; is a goldsmith and restorer, armorer, and blade-smith; and specializes in ancient forms of blacksmithing. He has been awarded numerous prizes. Now based in Holland, he works principally for museums and also restores European armaments for them.

Gocha Laghidze made his first creations, a chain mail and knight’s helmet, in his native country Georgia when he was just 14 years old. A history teacher instilled in him the love of metalworking and of traditional weaponry. “He showed me his own collection of historical weaponry. I was so fascinated by the beauty of the objects and the stories surrounding them that I studied them in detail, so I could make similar ones myself,” European Blades Magazine quotes him as saying. At the age of 21, Gocha was already a metal restorer in a national museum in Tbilisi. He says he remains inspired by the rich military history of Georgia, but has broadened his scope to European armaments since moving to Holland.

Other similarly skilled Georgians are working around the world. But today there seems to be no danger that the craft of making khanjali will disappear from Georgia, thanks a great deal to the attention, organization, structure, and craft network created by Jaba Bokuchava with the Knife Makers & Collectors Association of Georgia. Anyway, as Teimuraz Jalaghania commented to HomoFaber.com: “Society today often forgets about people like us, but real masters are stubborn enough to continue their work no matter what happens.”