Tbilisi calling – why India’s eyes are on the Caucasus

Despite a visibly growing Indian footprint in Georgia—from thousands of students to increasing investment and tourism—economic ties between the two countries remain underdeveloped. While India deepens its engagement across Central Asia and the South Caucasus, Georgia has yet to fully capitalize on this momentum. A new ambassador, direct flights, and potential trade talks could mark a turning point.

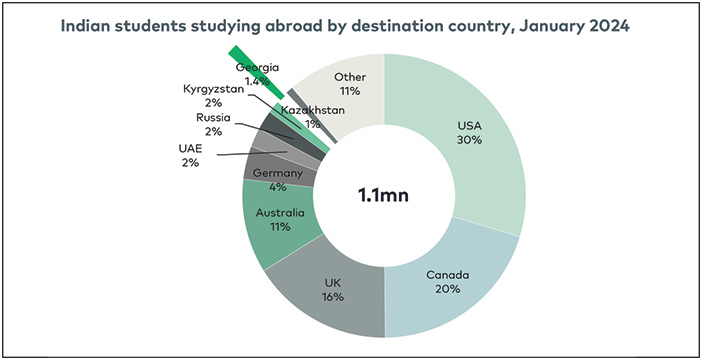

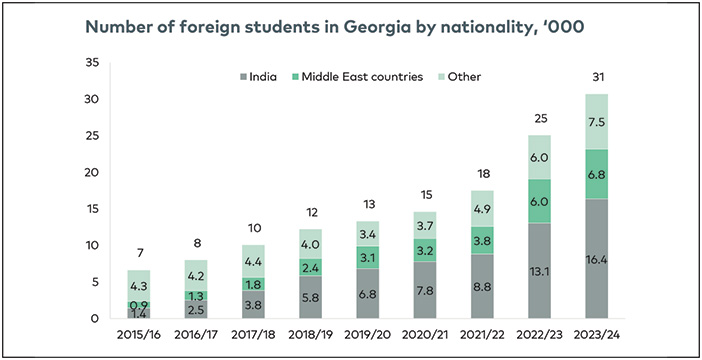

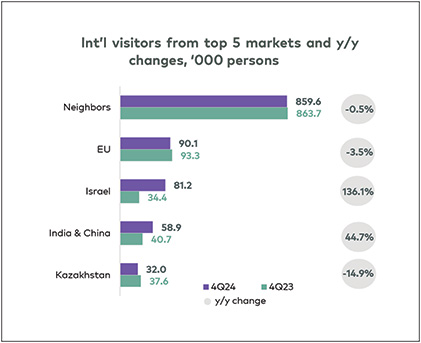

India’s presence in Georgia has significant room for growth if its track record in the wider Caucasus and Central Asia is any indication. Georgia already hosts more than 20,000 Indian students, sees busy streets filled with Indian Glovo, Wolt, and Yandex food delivery drivers, and welcomed 124,000 Indian tourists in 2024. Yet the India-Georgia business dialogue remains relatively muted—especially compared to India’s rising profile in Armenia, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan.

However, since December, India has its own Indian Ambassador to Georgia (instead of sharing the one in Armenia), and governmental and business visits are being exchanged. Plus, Georgia formally approached the government of India last summer to initiate negotiations toward a bilateral free trade agreement.

India’s strategy: quiet competition with China

India’s strategy in the Caucasus, as outlined in The Diplomat, a Washington-based international news and analysis online magazine, is to compete quietly with China’s expansion in the region and “unlike their overt rivalry in the Indian Ocean and Indo-Pacific, which is marked by military posturing and strategic competition … to avoid direct confrontation.” But the countries have parallel ambitions.

For India, the “program is to grow links via economic initiatives, infrastructure projects, strategic security and political alignments,” states The Diplomat. Currently, China is the region’s leading trade partner, particularly because of its Belt-And-Road Initiative and attendant vast investment, through which it has been aiming to boost its connectivity—seeking to create seamless transit to overseas markets by modernizing railways and roads.

Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia are, says The Diplomat, “vital nodes within an emerging logistic network.” These are the Middle Corridor, which will cross Eurasia, starting from Europe, traversing through Georgia and over the Caspian, then through Central Asia to China – and the route which India has been attempting to advance, the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC). This is a 7,200 kilometer-long multimode network of ship, rail, and road routes for moving freight from India’s port of Mumbai to St. Petersburg and Europe via Iran and the South Caucasus. The INSTC allows India to bypass insecure routes through Pakistan and Afghanistan. “In 2024, trade between India and Russia nearly doubled, reaching a record $66 billion, largely driven by increased use of the INSTC,” states The Diplomat.

It adds: “India is willing to work with all three South Caucasus countries—Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia—on this project. This is mainly because India lacks China’s financial leverage and relies on transit countries to invest or find sources of financing to turn this project into reality.”

Central Asia courts Indian capital

In the Caucasus and Central Asia, India has been building international business links steadily for years, in particular with the (admittedly large and energy-rich) economies of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. As a major competitor for any regional investment going, Uzbekistan is holding out a lot of lures. Evidence is the recent Tashkent International Investment Forum, which drew 7,500 delegates from 100 countries and secured over €26 billion in signed projects across energy, agriculture, infrastructure, digital tech, and mining.

While it may not help India’s immediate trans-continental transit ambitions, Central Asia does offer large markets. With its eye on India’s wealth, skills, and technology, Uzbekistan has offered land, support infrastructure, tax benefits, and cheap power to Indian companies. Bilateral trade is not vast, at under $500 million last year, but Indian companies have already invested in pharmaceuticals, renewable energy, logistics, and education.

Competing with the medical degrees offered by Georgia, Uzbekistan is catching up, with over 10,000 Indian students pursuing medical education. And it is also rapidly expanding in tourism: Indian visitor numbers last year doubled to 80,000. India also hosts a large Uzbek diaspora; the size of the Indian community in Uzbekistan is estimated to be 30,000, including students, according to the website of the World Trade Centre in Mumbai.

Kazakhstan leads in the region when it comes to corporate investment with 600 Indian companies now operating there, mainly in pharmaceuticals, mining, and food production. According to a press release from the Kazakh Ministry of Foreign Affairs, India has invested over $450 million in the country in the last 20 years, and bilateral trade now totals over $1 billion per year.

South Caucasus: parallel paths, different speeds

Nearer to home, Armenia, too, can boast of an increasing number of Indian tourists – around 10,000 out of a total of 180,000 in the first five months of the year. Student numbers are around 3,000, with medicine the most popular subject, followed by dentistry, pharmacy, engineering, and IT.

The reach of links is fanning out. Armenia hosts a diaspora of 50,000 Indian immigrants in services and the SME sector, the second largest community among foreigners. The country’s strongest links with India is through its supply of arms and defence equipment, with deals worth hundreds of millions of dollars. India, says The Diplomat, regards its close relationship as part of its “extended neighbor“ strategy in the region, by which it aims to balance the influence of other powers.

General bilateral trade between Armenia and India accounts for just $200 million but is diversified. And, land-locked Armenia, the least connected to the new trade corridors, has created an air corridor from India to Armenia for strategic exports to improve logistic services.

While Azerbaijan-India relations are on hold right now, its location makes it vital to India’s connectivity plans. It has a rail link with Russia, and has initially pledged $500 million for the overall INSTC network. Azerbaijan has been attracting Indian investment to its techno-parks as well as oilfields. A major campaign to attract Indian companies as well as those from elsewhere has centered around the country’s strength in IT, with more than $400 million being spent by the government alone in facilities and incentives.

Azerbaijan’s companies in pharmaceuticals, textiles, construction, and IT services are also increasingly becoming part of bilateral trade discussions. And the tourist attraction is growing—while Indians accounted for a relatively small share of total tourist numbers (8%) at 224,000 in 2024, they more than doubled the figures of the previous year.

Georgia: opportunity waiting to be seized

According to the Indian Embassy in Georgia, total Indian investment in the country—both direct and indirect—totals approximately $769 million. Steel, infrastructure, agriculture, and service sections are among the few sectors of large investment. Major Indian investors are Tata Power, Geo Steel (a joint venture of JSW Steel Netherlands BV, which is wholly owned by JSW, India, and Georgian Steel Group) and Jindal Petroleum (an oil and gas explorer). Tata Power invested about $166 million, jointly with other European partners, in the 187 MW Shuakhevi Hydro Power Project (HPP) in western Georgia—the largest hydropower plant to be built in Georgia over the past 50 years.

Less well publicized is Georgia’s participation in India’s famous film industry, Bollywood. The Georgian government launched an incentive program offering a 20% cash rebate on qualified expenses incurred for film shooting in Georgia. This has resulted in many Indian films being shot in Georgia, including Race 3, Pyar ka Punch Nama, and Mom.

Currently, bilateral trade between Georgia and India is relatively small. Last year, according to online international data aggregator Trading Economics, exports totaled around $29 million, most of which was fertilizers ($22 million) followed by copper ($3 million). Imports totaled $104 million, with pharmaceuticals ($28 million), machinery ($16 million), and electrical and electronic equipment ($11.5 million) the largest items.

The main areas of business growth with India are likely to remain education and tourism. Forecasts for Indian student numbers at Georgian education establishments from investment bank Galt & Taggart are for a possible 31,000 by 2028, which it estimated (last year) would generate around $160 million in annual revenue.

The introduction of direct flights between New Delhi and Tbilisi by IndiGo in August 2023 has enhanced connectivity, leading to a substantial increase in Indian tourist arrivals. With the subsequent increase of flights and tourists, Indian companies, including Unique Mercantile India and Apna Punjab, have shown interest in developing four- and five-star hotels and operating professional golf courses in cities like Tbilisi, Batumi, Tskaltubo, and Mestia, according to the Georgian Ministry of Tourism.

Otherwise, to date, the only other area publicly targeting India is investment funds. Plans for a $50 million Europe-Asia Investment Fund to attract investment from India as well as the Middle East were announced early last year. The talk was of investing in Georgia’s renewable energy, development, and hospitality sectors – all areas where India has world-class companies.

There would seem to be plenty of scope for more entrepreneurial interest. Georgia is party to a number of free trade agreements, most valuable being with the European Union. With the U.S., although there is no free trade agreement in place, Georgia benefits from the U.S. GSP Program, which promotes economic growth in developing countries. This program allows certain goods from designated beneficiary nations to enter the U.S. market duty-free. Approximately 3,500 products are eligible for duty-free entry, yet in 2023, only 1.8% of Georgia’s exports to the U.S. comprised GSP-eligible goods, indicating that the program was being underutilized.

Further foundations for growth are Georgia’s four free zones: the Poti Free Industrial Zone, the Tbilisi Free Zone, the Kutaisi Free Zone, and the Hualing Kutaisi Free Industrial Zone (adjacent to the Kutaisi Zone). A further one is scheduled to open in Sagarejo next year.

Georgia’s links with India go back into antiquity. According to Indian historian Arunansh B. Goswami, as quoted in Georgia Today when on a visit to Georgia a couple of years ago, he spent time researching the ancient trade route linking the Transcaucasus with India. He found this: “Georgian King Erekle II (of the Bagrationi dynasty) asked an Armenian merchant based in India, Jacob Shakhamirian, to bring ten thousand Indians to Georgia. He wanted the Indians to teach the art of processing of sugar cane to Georgians and also assist in the foundation of the loom factory!”